Nine years ago, while recovering from a serious health crisis, the British society photographer Dafydd Jones decided to return to his archive of negatives and print a few of his old party pictures. Mr. Jones had spent three decades documenting the social scenes of British and American upper classes for The Tatler, The New York Observer and Vanity Fair under Tina Brown and Graydon Carter, but the frenetic pace of society photography had never given him time to look back on his own work.

In 2020, he published his first book of these photos, “Oxford: The Last Hurrah.” It was a surprise hit, prompting Mr. Jones to look back at his nights in the 1980s and 1990s, when he rubbed shoulders with Manhattan’s rich and powerful. These pictures of a bygone era, both glitzy and seedy, have been gathered together for the first time in a new book, “New York: High Life / Low Life,” available now in Britain and next month in the United States.

Mr. Jones spoke via video chat from his studio in East Sussex, England. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

In 1988, you left the London society circuit and moved to New York for a month. Why did you decide to uproot your life?

I’d never planned to be a social photographer. I just found myself in that situation and realized it was a really interesting world to photograph, and no one else was really covering it in a journalistic way. I was going to May balls in Cambridge, Oxford, Royal Ascot and the Derby, and there is a fixed calendar. I had a fantastic opportunity, but I suppose after you’ve been to Ascot eight times. …

Tina Brown invited me over for a month, just to see what it was like. I arrived at 4 o’clock in the afternoon at J.F.K. and went to a book launch at 6 o’clock that evening. It was a whole new world to be shooting for Vanity Fair.

Were the parties in New York very different from London?

I never did see anyone asleep at a party in New York, whereas in London, you’d always find someone dropping off. Years later, I realized: “Hang on, these people were all on something. That’s why they suddenly come to life at 1 o’clock when they ought to go home.”

People in New York were more paranoid about where they were sitting at a party. There were people around with loads of money, who’d made it very quickly. And there were some who were quite what I would call WASP-y — you know, So-and-So the Third — and they would always try and impress on me their American aristocratic credentials.

What do you think your subjects thought of you?

I probably was perceived as being excessively polite. And actually, that can get you quite a long way. In all sorts of situations, just being polite — nice, you know? That probably distinguishes me from some other photographers. At one party, I remember another photographer yelling abuse at the P.R. And I remember a photographer punching a P.R. person at an event I was photographing in New York. I had never seen that anywhere else.

Did you ever get into trouble for publishing something unflattering? Or were people less controlling of their image back then?

My editor, Richard Buckley, wanted me to go to the Madison Square Garden dog show and cover it all week. I said, “Aren’t there any parties happening or something, anything that’s a bit different for these dog people?”

At the party at Barbetta, they’d made the canapés to look like little dog biscuits or something. And the dogs did make a lunge, and there was a sort of incident between the dogs and canapés. And Brooke and Iris [Brooke Astor and Iris Love] happened to be standing together when it happened.

Tina Brown was the editor, and she just ran that picture. Afterward, they both asked for prints, Iris and Brooke. And Brooke said to me, “There’s such a funny expression on Dolly’s [her dachshund] face.”

And she looked me in the eye as she said it, and I knew she was thinking about her face as well. They were the epitome of High Life — kind of equivalent of New York royalty, really. But I can’t imagine if you did a picture like that today. People would be a lot more nervous about it appearing.

Most of the photographs feature the uptown social set, but you went downtown, too. There’s a photograph of Robert Mapplethorpe at his 42nd-birthday party, shortly before he died of AIDS. How did you find yourself there?

I just had it on my list: birthday party, Robert Mapplethorpe. I didn’t know he was ill. I got there, and it was already quite busy, a huge loft. I realized pretty quickly that there was a sort of down atmosphere. And I think I turned my flash off. It felt quite intrusive, being a photographer there. I could see he was ill. And I tried to take the nicest possible pictures of him, which actually weren’t what the magazine wanted. At the time, I thought I hadn’t done a good job because my pictures weren’t published, but I was happier within myself.

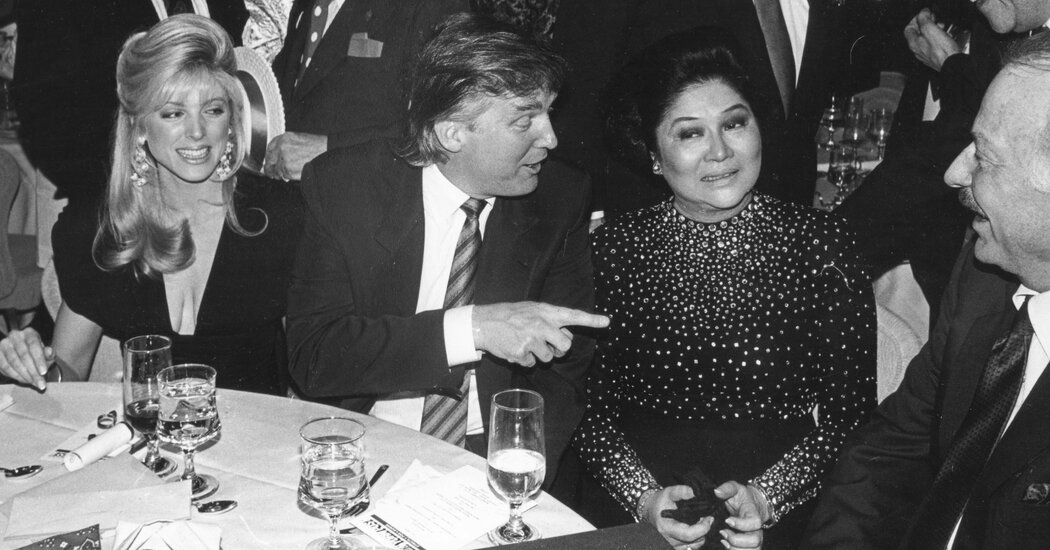

Some of the people in these photographs would become quite notorious: Rudolph Giuliani, Jeffrey Epstein, Donald Trump. What were your first impressions of these men?

When I first came across Donald Trump, I thought he seemed quite a brash, crude person, but I didn’t have anything particularly against him. In my introduction I mention that he gave a party for Benazir Bhutto [the former prime minister of Pakistan], and I’d got it wrong: It wasn’t his party. It was a party given by Reinaldo and Carolina Herrera for Benazir Bhutto at the Plaza. Donald demanded to know why she wasn’t staying at the Plaza, and he offered her a good deal the next time she wanted a hotel. I thought it was Donald’s party because that was the way he behaved, as if he was hosting Benazir.

Tell me about the photograph of Jeffrey Epstein from the opening of the Harley Davidson Cafe in 1993.

When I got there, there was this great scene outside. A crowd of people, and it was raining. Donald Trump was there with his children — that’s Donald on the left of Jeffrey Epstein.

Epstein is on a balcony looking down below. He looked extraordinary — sort of wolflike, really, but he was, relatively speaking, a nobody. That picture was a striking image to me.

Is there an image that captures the essence of New York from that time?

My life in England as a social photographer was almost a kind of Bertie Wooster existence by comparison to New York. There was the AIDS crisis and the crack epidemic. I was pickpocketed on the subway, but I did love New York.

There was a sort of annual thing that used to happen, the elephants would come to the circus, and they’d come through the tunnel from Queens. It would happen quite late at night when there wasn’t much traffic or anyone around. And so I trailed along with the elephants, and they stopped to have a rest — I think this was 33rd Street — where there were sex shops and things, and the steam coming out of the manhole cover. It is a bit surreal, seeing elephants walking through Manhattan.

Sumber: www.nytimes.com